This webinar session featured Euan Adie, CEO of Overton, as the guest.

Overton is the world’s largest searchable index of policy documents, guidelines, think tank publications and working papers.

Euan spoke on the topic: Enhancing the Policy Impact of African Research: Strategies for Visibility and Influence through Overton.

African researchers and other attendees learned how to make their research more visible to policymakers and track its impact using Overton. They also got tips on engaging with policymakers and saw examples of how African research has influenced policy decisions.

Watch the recording

The slides are available here: https://africarxiv.ubuntunet.net/handle/1/1768

Screenshots from the Webinar Session

This webinar series is co-organized by: UbuntuNet Alliance and Access 2 Perspectives as part of the ORCID Global Participation Program: https://info.orcid.org/global-participation-program/

Speaker’s profile:

Euan Adie, CEO Overton

ORCID ID: 0000-0001-9227-4188

Euan is the CEO of Overton, a London-based company that tracks and indexes the research, ideas, and influences behind government policy worldwide.

Before founding Overton, Euan established and led Altmetric, a company that tracks the attention paid to scholarly works online. Altmetric was acquired by Digital Science in 2015.

He has also worked at Nature Publishing Group and as a researcher in medical genetics at the University of Edinburgh.

Questions discussed during the Q&A session

1. What inspired you to start Overton, and how has the journey been so far?

I was always interested in how research is used outside of academia – where it is used by practitioners in the real world, or in patents, or to shape public understanding of an issue.

Then Brexit in the UK and COVID more generally made me really think about the challenges of evidence led policy. I thought that there were things that you could maybe make easier through collecting data and doing grunt analysis work automatically.

2. How does Overton work, and what makes it different from other platforms that track research impact?

Overton is centered around policy documents and policymakers (rather than scholarly journal articles or anything else) and so their relationships with each other and out to academia, the media and elsewhere is the framework for how we interpret evidence, influence and use.

We’re the world’s biggest database of full text public policy documents, so we tend to have a breadth and depth of coverage that others don’t.

3. What are some of the key trends you’ve noticed in how research influences government policy worldwide?

These aren’t trends per se, but I think there are lots of things that people working with policy know or suspect but that are still surprising to outsiders and that come out in the data.

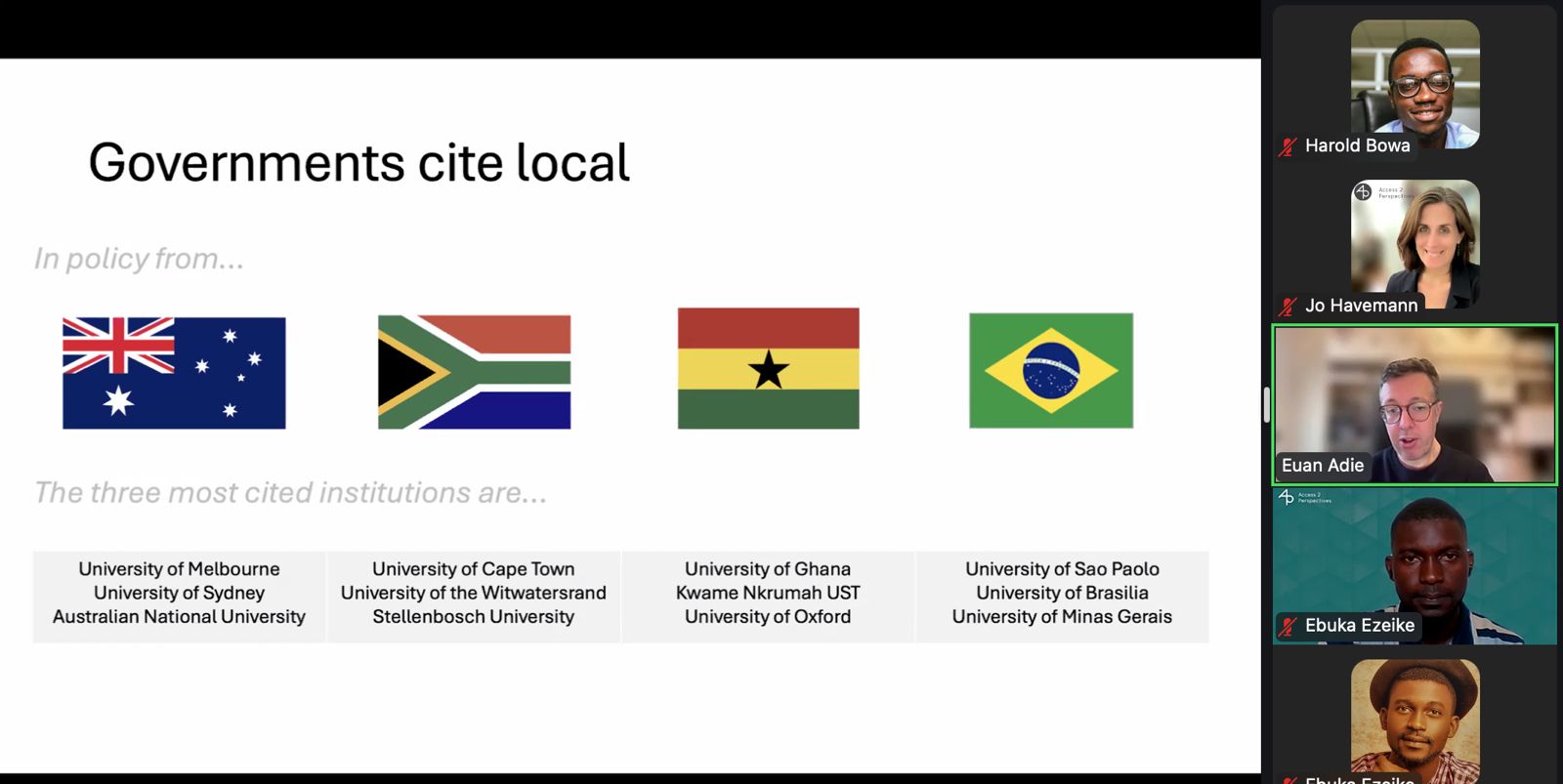

One is governments citing locals – this has always been the case, but more so now (US policy isn’t based on Chinese research and vice versa, for example). There’s a bit more of an effort to pull evidence from a wider group of people within a country: in the data you can usually see that governments end up calling more on universities and institutions based in the capital city, for example.

Generally the idea of policy based evidence is gaining traction, even if people don’t always agree exactly what it means (the policy isn’t really based on evidence: policy is political and there are lots of other important factors going into decisions. So the name is a bit misleading!)

4. How do you see the role of Overton evolving in the next few years, especially with the growing focus on evidence-based policy?

We’re really keen to look at what we can do from both the supply (research) and demand (government) sides. We already work with both groups and I’m keen for that to continue.

Personally I’d love to start thinking about credit and incentives for academic/policy engagement: it’s not a free activity! Time on both sides is spent and potentially wasted. As an individual academic if you care about your career that time is probably better spent on teaching or research. For policymakers you may need a useful answer at short notice and despair when you speak to academics who are used to hedging and caveating findings, or who feel like they need much more time and money to be able to answer a question.

5. What advice would you give to African researchers who want to maximize the impact of their work on public policy?

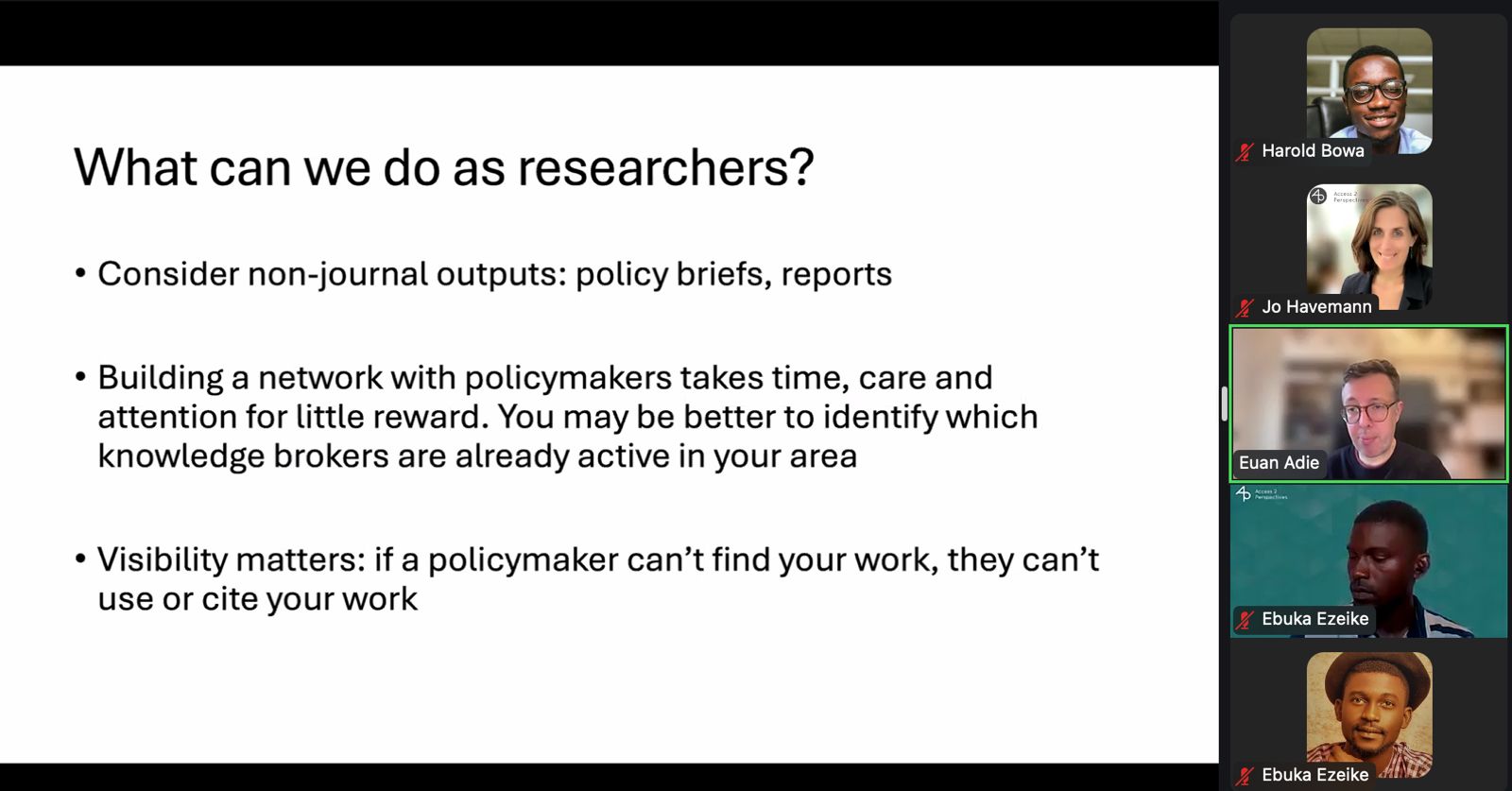

I think researchers have a lot of options, some taking much more time and effort than others – if you need to balance policy outreach type work with existing commitments then my suggestion would be to find other people and organizations already working with policymakers and to chat to them, you don’t want to start from scratch.

6. It is observed that social sciences are more or heavily cited in policy. How do we get other sciences (Physics, Chemistry etc) to be cited more in policy?

I think this mostly comes from lack of demand. If that’s OK or not is a different question! Either governments don’t need physics research when designing policy (in which case we shouldn’t try to push it) or they need it but don’t realize that (in which case it’s the job of academics to demonstrate what’s available and how it might help future policy questions)

7. We have few institutions in Africa whose research output are cited in policy. How can we increase the number of these African institutions?

I think for organizations thinking about this the key is to think about the whole system and to target efforts on where they might have the most useful impact.

It’s worth remembering that impact is different to policy citations: a single good use of research somewhere might have a huge impact, while a hundred throwaway uses may have very little. So if the aim is impact we need to think of quality, not just quantity.

More specifically, though, I’d be studying if existing brokers or interfaces that sit between universities and local government (at the national, city or state level) exist, and thinking about how they can be nurtured or created if there aren’t any already. At that point you need buy-in from both universities – to ensure relevant research is produced and made visible – and government, to actually look for and engage with it.